Recently I have some mounting problems and stress at work, and while it would be easy to write it off as unfortunate circumstances, I felt like I need to dig into the causes much more to understand and try to fix them. It seems that it’s not just me having problems, my entire “industry”, the Academia has some fundamental difficulties. Can hardly say things about other fiends, but I have some overview of the atomic physics research done around the world, and nothing indicates that the issues are confined to physics alone. These are the problems I try to explore here.

I’m a physicist, working still as such, in my 5th year as a post-doctoral researcher (this is my second post-doc position). Altogether I think I am in physics for about 14 years now (or 20 if we count the high school where I was already conquered by it, just wasn’t quite aware of it yet).

At my lab I felt there are some things that could be done better, to have a better group and research quality. I tried to bring some ideas from my old lab, from the startup world, from computer science, and my ideas what research should be like. Most of those changes were shot down, and many of the changes experienced became very frustrating, I felt like I’m on the wrong track.

Recently I got to read Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams, and while it is aimed mostly at the IT industry, plenty of things are completely general. It was one of those reads that I was on the verge of tears in the end, because recognized so many things that went wrong in my environment.

One of the most important thing I felt was that our lab should be a team, a consciously cultivated team to really achieve its potential. The upper level always indicated that they took the fact that we work in the same lab as a sign that we already have a team, and that’s just one of the problems.

From the book it feels that the entire success or failure of projects mostly depends on the people and their connection with each other. Looking at the Academia, it feels like almost everything is set against building a great team. Not consciously, many people have lofty goals of efficiency, productivity, and similar things, but they go around naively to achieve those, and in the same time they destroy the resources that would create efficiency and productivity and creativity.

Looking at Peopleware’s Chapter 20 about Teamicide, they list a number of things that inhibit team formation or crush working teams:

- defensive management

- bureaucracy

- physical separation

- fragmentation of people’s time

- quality reduction of the product

- phony deadlines

- clique control

I have experienced pretty much all of this in the labs here. Defensive management, people cannot be trusted to make the right decisions, because it reflects bad on you, so you have to make the choices for them and push it through, generally thinking that the people you got for the job are actually incapable of doing it. Bureaucratic, have plenty of stories about that, everyone has, even worse in Taiwan than general. Physical separation is less of an issue here, we are all in the same office. Fragmentation of people’s time, even when working on apparently “priority project that you need to drop everything else until it’s done”, it’s still “hope in the same time you can help out with X & Y”. Quality reduction, this is the worst one for people who believe in their abilities, having to work on something that I know it would be worse by far than other solutions I could bring, but it’s squarely ruled out, and now I’m feeling I’m spending my time building essentially waste. Phony deadlines, there are plenty of them, because people think that setting a deadline will make people work harder, which is missing the point – the hardest workers are those who are not pressured and have been given worthwhile goals”. Clique control, stopping efforts that would mainly be about knowing each other, effortless communication, and feeling that we work “together” instead of “in the same space”.

In later chapters they also point out a few more parts. High turnover poisons everything. Management don’t invest in training, people are not invested in their work, it’s just something “temporary”, why to give it all the effort (consciously or subconsciously)? Academia is almost designed for high turnover. Masters students for 6 months to 2 years max. PhD students from 3-8 years (though the long time is more problematic in terms of exploitation), postdocs from 1-2 years, and you are expected to move on and move up. Become a professor “somewhere else”, and start your own high turnover lab. The whole thing is quite often just milking the current place for results, or milking the new workers for their energy until they leave, because they are known to be leaving soon.

This also gives rise to thinking of people as building blocks. How often it is heard that “I need more masters students to do this project”, or “you should hire a post-doc for that”. Not ability, but function.

There’s often very little training about generally useful things, because of the high turnover is so etched into people’s mind: if my student will leave soon anyways, why teach him, or why teach the group in general something that is not immediately useful for their work? Why waste time with that?

There are lot of other problems as well, which mainly comes from how people get their jobs. To run a research group and become a professor, one needs to have: academic skills, teaching skills, management skills.

The first one people demonstrate through papers, passing exams and so on, so usually they have indeed good skills (don’t want to dispute that). The other two skills are on the other hand never tested, and just taken for granted, taken as the “easy” part. On the contrary, most people who think they can manage people (me included), are naive and make a lot of mistakes, even be completely counterproductive. Many professors are terrible teachers and managers, while they think they are doing okay or even great, so they don’t have to examine their level, nor improve on it.

Because of these things, that are so ingrained into the Academia, I’m even surprised that there’s so much success as there is. I would argue, many times the success is temporary and because of people’s skills to persevere against the odds. In some subset, actually, things fall into place. In my previous research group at Oxford, things were like that: professors let students to experiment and try things even if they don’t agree or see the point at the time (within limits, of course), people stayed on after their PhD, or spent their masters there as well, so much lower turnover, they took the bureaucracy out of the picture so if I needed something I just had it, no overtime because everyone knew that people need a life (and dinner at college starts at 5:30, so got to leave before that), and natural team building, like the tradition of whole departmental coffee (morning) & tea break (afternoon). We talked about everything, got to know each other, exchanged ideas, never got stuck in our work. And everyone was happy. I think I got spoiled by that, and took such environment for granted.

Of course, most of the things I mention here are not new nor original observation. To understand the situation, I started to read some books that supposed to guide new professors, for example New Faculty: A Practical Guide For Academic Beginners. I was wildly agreeing with the picture they paint of the problems in the preface, and starting to see some of the things a little better, while it still feels as if it falls short: most people trying to fix the problems by better assimilating themselves into the existing community, instead of shaking up the way “things are done here”.

That’s not necessarily bad, as another book I got recommended, the Orbiting the Giant Hairball showed me. There are a lot of resources that even a troublesome environment can provide. Still, how much one’s energy should be invested into fighting the system, and how much into the things we want to do to change the world?

Crossover Labs

Looking at the whole situation, my last 5 years were good lesson in life, while they left me almost nothing to go ahead in Academia. Joined labs that were stuck, or still building up, so I learned a lot, but haven’t got anything published, which is almost the single thing they need in the Taiwanese system to enter the professor level. Also, as I mentioned, most of the problems seems to be by design, so it feels I can do relatively little from the inside, if I want to change things. And I really do want.

I don’t want to leave physics behind either, research is what I’d like to do.

Instead, let’s think of something crazy: there were really successful non-academic research laboratories, let’s take Bell Labs. Unfortunately they have stopped fundamental physics research, but what if that tradition would be revived? If Bell Labs needed a powerful mother company to run it, how would we do a similar thing “21st Century Style”? Can we get some inspiration by non-conventional research and technology, learn from the old Bell, from SpaceX, from the HP garage, from the MIT Media Lab, from firms like IDEO, from Formula 1 teams, from Japanese innovation at Honda/Toyota/others, from IBM, from Sparkfun? These are all a bit wild examples, while I believe all of them have some insight that will or have changed me for the better.

Can I find a place where I can test my theories of research, how the 20% time would work in a lab; finish side projects that are right now dissuaded and covered up with just throwing grant money on it; see how people would probe the universe without the pressure to publish or perish; when people can change fields and become useful in research in a way they find fitting as well; when learning and training are priorities; when the quality of results is not been sacrificed…

I kinda think that I could do this in one obvious, but very scary way: I’d have to start it myself.

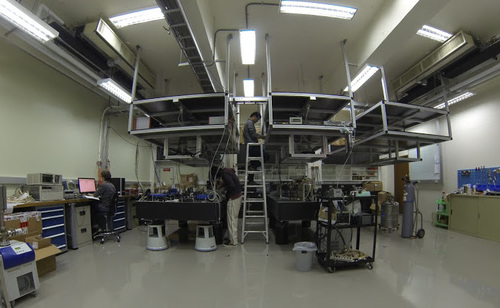

Thus it seems the path forward is taking my time at the current position till the contract runs out at the end of this year. Learn as much as I can. Do things as well as I can. Than based on all those experience, found a new laboratory, let’s give it a working title of Crossover Labs, and see what can be done on a shoestring.

Set up a laboratory that puts research first, based on the people. Make it so that it can fund itself from its byproducts in good Cambridge style where successful research is spin off into companies. Let’s have a place which doesn’t have to push people to do things, because they want to do, just get out of the way of them kicking ass. How to do this will need a lot more thinking and will definitely write about it more.

It is easier to say than to do, so if this vision is something that resonates with you as well, then let me know, that would be already helpful!

And I’m a bit sad that I got to the stage of “calling in well”, but it feels it has to be done:

Chances are you’ve heard of people calling in sick. You may have called in sick a few times yourself. But have you ever thought of calling in well?

It’d go like this: You’d get the boss on the line and say, “Listen, I’ve been sick ever since I started working here, but today I’m well and I won’t be in anymore.”

– Tim Robbins: Even Cowgirls Get The Blues (via Peopleware)

Thanks David and Nathan for feedback before the publication of this post.

3 replies on “Academia is failing but not for everyone”

I kind of feel the same as you do, but because I’ve chosen a career in industry, I am not in a position that justifies any comment about research in academia.

But I think

I kind of feel the same as you do, but because I’ve chosen a career in industry, perhaps none of my comments about research in academia can be justified.

But I wanted to give my feedback on one of your paragraphs:

“There’s often very little training about generally useful things, because of the high turnover is so etched into people’s mind: if my student will leave soon anyways, why teach him, or why teach the group in general something that is not immediately useful for their work? Why waste time with that?”

This is a sad thing, and totally disregards the purpose of education. I actually fell into this fallacy when I was in grad school. At that time I was too obsessed by code development, and tried to persuade the PI to enforce some rules in favor of efficient team work, even if the rest of the research team has little understanding about software engineering. The reaction from my adviser was a gentle reminder: “It’s a good thing to have an organized code base, but in school, education is also important, and students need to gain experience form doing and erring.” Indeed, although there’s nothing wrong to be systematic about code development (we do computational things), it should be respected that everyone is in different stage in his/her learning path.

I guess the intentional omission of educational efforts in some research labs could be caused by over-competition. It’s generally unrealistic for a PI to take care of tens of students. I think even an experienced manager can’t function well with a team of more than 10 programmers. It’s extremely challenging to work with a big research team, the work of which is much more intellect-intense than programming, composed by PIs, postdocs, and grad students. Over-competition can be one of the most prominent issues. Luckily I’ve only heard about all those troubles, and not experienced with them myself.

Hi Yung-Yu,

Thanks a lot for your comment, it’s good to see different points of view and experience.

You are right, over-competition seems like a very apt explanation for a lot of things that happen in the labs. People put minimal effort into everything, because they think that everything above that is a “waste”, while it’s actually not taking the long term into account.

I was trying to get some (minimal) coding standards included in our thinking, because for example spending a little more effort in writing code will save a *lot* of time in reading the code later. Now I’m spending a lot of time writing explanation and documentation (separate from the code), months or years after the code, because finally the higher ups decided that keeping the knowledge is important.

Also, thinking more, this shortsighted short-term thinking is in everything. Many of the problems I experienced for example could be handled with some effective mentoring (because I need to learn more too, not just to rock the boat, but the effectively make a difference). But mentoring, and taking any interest in students and employees are explicitly labeled as waste of time….

As a punchline, I was just fired from this lab this week, so it is definitely time to get my game on, and grow where I can, not just were I am :)

If you are in Taipei, would love to meet up for a coffee some time, if you are interested, hit me up any time at imrehg@gmail.com :)

Greg