Experimental physicists have to be the jack-of-all-trades, even on a good day, but building a new laboratory, on a budget (for any definition of “budget”) and with a limited team, is an exercise that would test anyone.

For my field, atomic physics, one needs a lot of different expertise: vacuum systems, computers, electronics, machining, optics are among the ones first to my mind. Today I’m looking at one of the tools that we are using for the last topics: optics.

In some ways, optics is pretty straightforward (both geometrical and diffraction optics), many of the calculations one could write in Python/Numpy just as well, as any software can do it. They are just pretty tedious, and there are a lot of them, optics is not a new profession. Some optics design software is very useful then, and there are not that many of them, lots of work goes into the ones that exist, thus they can be extremely expensive. One of the industry standard seem to be Zemax, and many lens manufacturers provide the specs of their lenses in a Zemax format – though it is fortunately just a relatively simple text file. On the other hand, its cheapest edition is $2500, and goes up to $9500…

Another serious competitor is OSLO (Optics Software for Layout and Optimization) which is still very well known, and fortunately for us, has a dumbed down (limited number of surfaces, not all the functions available), EDU version, for free. It even runs on Linux with Wine.

I instinctively resist any software in science & research that is not free & open source, because I feel that it closes some people out, though had to use something, and in the meantime I have grown to OSLO quite a bit.

Using OSLO, I have found that one big advantage of these software is their catalog: the glasses (oh-very-important for optics) and stock optics of different companies. This alone makes everything much easier.

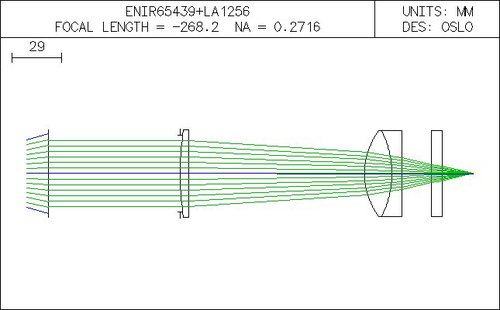

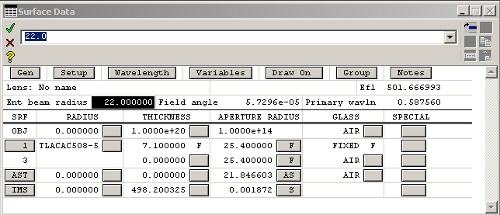

What does the lens designer software do? You enter the parameters of some lenses by defining different surfaces and materials & distances between those surfaces, give it some lightbeams, and see what comes out of it. Most of this happens in this window:

After these settings, one can run a number of different analytics code, checking the performance and behaviour of the system by calculating a bunch of physics parameters, or can modify the system to optimize that performance one way or another.

This is where the number 1 strangeness – and big bonus – comes in: OSLO can be scripted in a language called Compiled Command Language (CCL), which is a subset of C; and not just scripted, but the whole program is written on top of the CCL compiler (as I understand)! The result of this is that:

- Your scripting can be just as powerful as the entire program, since both sides have the same functions accessible

- There are a bunch of scripts included in the main version and even if CCL itself feels poorly documented, there are plenty of examples to learn from

- Once your script is compiled for OSLO, it can be totally part of the system, your own menuitems, options, defaults, everything

- Scripting is not just bolted on later, but the whole software feels like a result of “eating your own dogfood“, resulting in a much better experience.

Optics design is tedious, so once I figured out how to do the scripting, everything just become nicer. Haven’t had time to do a lot of things, but the script I have so far is open source, and hope to add other things later.

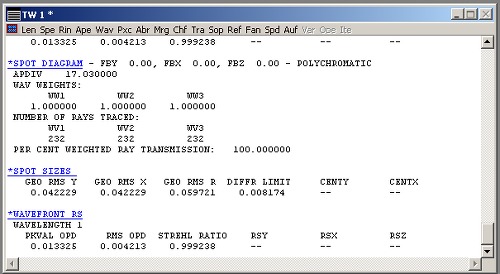

From the programming point of view, there’s one more strangeness. Starts with that the output of numerical calculations looks like this:

Those are all results from different functions, calculating spot sizes and wavefront distortions and what not, and those can be run from your own script – but the return variables are just printed. And they are a table. Those are table values that have to be accessed, so for example if I want to have the Strehl Ratio there, I would have to assign the value of something like “c1” to my internal variable – c for 3rd column, 1 for first row. Though to be this simple my code would have to clear the existing table before running the wavefront function correctly. This results in a lot of counting on the screen to see what row/column output of a function I want to actually use.

Internally, I think most of the calculations are following a finite number of rays. Finite but very high (~1000). The big problem, that could get the unsuspecting people (like I was), that what looks like a continuous calculation, is actually digital. For example if I set an aperture within the system that cuts into the incoming rays, and keep changing the aperture size (which is just a real number), the output results don’t really change unless I exclude or include some of the beams that OSLO is using for calculation – thus the result is changing in steps, and hard to trust. I guess there should be a setting somewhere to change the number of rays used, but still trying to find it.

It is one clever program though. The input and output parameters of a lightbeam are really connected by the system, since practically speaking, the optics are just transforming some parameters of the beam into other values, thus if I set the input parameters, the output is given. With OSLO they do this in a way, that the code just follows what parameters you have changed last time (input beam size? output image angles?…) and that will be a fixed variable, while everything else is adjusted. Some parameters disappear when others take certain values (set your object very far away? then we don’t have to let you set your object size, since it’s not important, instead give you a viewfield angle). It’s funky when I figured it out, but took a while…

I don’t know how much longer I’ll have to use it at work, but this looks something that really tickled my interest learning optical design much more, and once I have the hang of the quirks, it’s pretty neat. If anyone’s interested, there’s a pretty useful mailing list.

Now if only there was an open source solution… : ) (please drop me a line if there’s a good one)